London The Song, London The Poem

I ended up getting more than bargained for recently while revisiting this special song ‘London’ (Above) by Sparklehorse. Introduced to me in 1995 by a friend at University when it was released as a b-side. I’ve kind of orbited Sparklehorse in the intervening years, hearing some delights but for whatever reason, not quite delving further to this point in time.

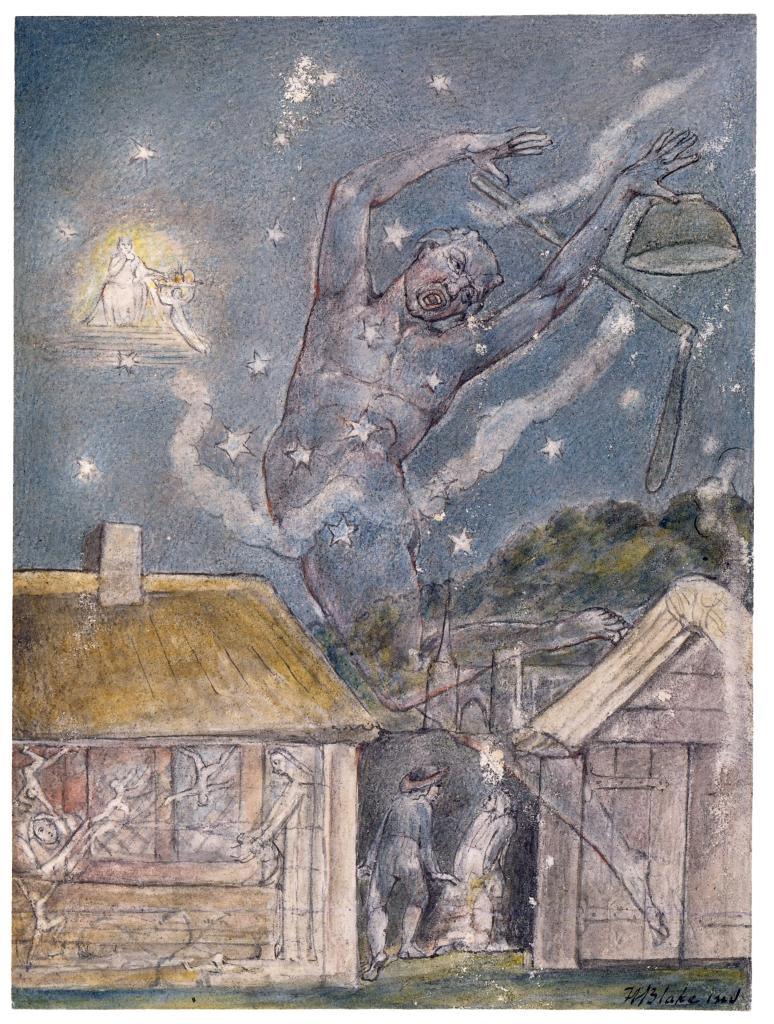

Although I was introduced to the song almost thirty years ago, it has maintained itself in my consciousness even while I did not have a copy I could play. I recall for years it wasn’t on Youtube and I would think about it occasionally, it had a simple yet alluring call on my mind. When I finally found it again, I was able to connect once more with its delicate and bleak but somehow serene lyrical telling of William Blake’s heart-rending poem of the lives of the downtrodden of London on the cusp of the 19thC.

In reality and in the wider sense of the health of our contact with life as a species and as individuals – much hasn’t changed since then, the pressures of human existence are as grave as they have ever been – yet still the will is there towards that spark of love, imagination, that feeling of connection with a vivacious flame of existence’s impregnation of life with itself. As we’ve oft quoted the great poet Dylan Thomas ‘The force that through the green fuse drives the flower, drives my green age’.

*

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Wiliiam Blake, London

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear

How the Chimney-sweepers cry

Every blackning Church appalls,

And the hapless Soldiers sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls

But most thro’ midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlots curse

Blasts the new-born Infants tear

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.

One of the things that’s so attractive about Sparklehorse leader Mark Linkous’ musical take on this eponymous poem is its simplicity. It is artfully simple, never changing chord sequence, relying for its chorus instead on a simple instrumental melody line shared between cello and trumpet, that holds gently and soulfully through the melodic minor space of the chords. Linkous’ vocal harmony is perfectly pitched as the sentience of these destitutions of times, lives and circumstance given words through Blake’s lucid and resonant capture.

This epic of words, London – has inspired many with its knuckle-rooted rhyme and meaning. Taking us into an already-established urban nexus of humans trapped by lives of largely unbeknownst excision from available directions of freedom and larger realities – to say nothing of love, which could be thought of as one of the places from which Blake speaks in the first place. Both the river and the streets are ‘chartered’ – the very space, the natural course is given for the existence of humans only as an aegis of a state power. The very imposition of structurality in abstraction-as-ownership and power in the lives and terrains of humans (never mind animals).

In a striking confluence, T.S Eliot arose to a similar psycho-geographical conclusion in The Wasteland from 1922:

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

T.S.Eliot – The Waste Land.

Blake (in 1794) is utterly scything of the established order and structure of human lives, as well as the obvious, penetrating injustice.

And the hapless Soldiers sigh

Wiliiam Blake, London

Runs in blood down Palace walls

But surely nowhere is Blake more revealing than when he lists through which the sounds and cries that tell him of the human life of the mind. In terms from Deleuze and Guattari, it would be said that Blake identifies the production of stratification through the expression of human sound.

In every cry of every Man,

Wiliiam Blake, London

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear

*

Eternity / multiplicity / perception

Alongside this, it is vital to be cognisant of the openings in Blake’s lambent poetry and construction, as with something like The Marriage of Heaven and Hell composed in 1790. While partly engaged along the lines of extricating concepts of spirituality from the Christian church, it is where one of his most extraordinary aphorisms arises, ‘Eternity is in love with the productions of time’.

Such an extraordinary cosmic marker – if nothing else, opens up a number of spaces. Daring to invoke Eternity as a cosmological entity with some kind of relationship to the outcomes of chronic time and its pervading travail of worlds. It is also striking, that in using production as the operative term, Blake opens up to abstract production and the space of pervading intensities.

I recall reading in something Mark Fisher wrote (it may have been the book of his PhD thesis Flatline Constructs) that we needed to be open to the idea beyond our traditionally conceived structures, that even the most heinous of acts and situations in some way was a ‘good’ for someone or something else, as the reverse would also be accurate. The thought also occurs of a line from one of the Castaneda books which resonates here that when a person is crossing a threshold of some kind (in terms of being, perception, intensity) something ‘…makes a bid’ for the energy / power involved.

As I understood it, Mark was trying to make sense of the apparently senseless in the vast scale of human stupidity and tragedy and doing so led to the idea of outcomes and circumstances that – in their actual reach and extent – transcend any normality of conceptualisation in terms of the connection, termini and modality of things that can have little other capable explanation. While this is very much my own recombining of this thought now, to my mind it brings the following two conclusions that need to be stated / re-stated.

The first, that our primary habituated forms of perception need to be reconsidered as during the course of lifetimes, it is malleable, and recurrently influxed with instances, threads of meaning and realisation that shatter that previous order of (in)completion. I think this is why Fisher wrote about The Weird and the Eerie in the last published work in his lifetime. He was excavating the edges of our defined structures of perception around the anomalous, those things that challenge cognitive ‘routineity’ and profoundly so. A recognition is also required that most of these interruptions (especially the most radical or ‘irrational’) are quickly overcoded and re-normalised in any number of ways to re-conform with the story of our personally consistent reality – endlessly repeated, where materiality is truncated from abstraction and abstraction is reduced to more inert forms both lingual and as images of thought.

The second, that alongside this understanding is the requirement for a greater degree of openness towards the idea that there are different iterative aspects to agency that we cannot easily know. Our image of our lives tend to be curtailed in a way that we are only ever encountering the outcome of events; left with the anger, the offense, the disrespect, occasionally the elation, the joy, the outpouring, without really knowing or understanding how these things arise in terms of the frequencies, transformations and encounters of our beings and their constituents. Some resonant, deep wells and seas of contact with abstraction, that are also habitually beyond us.

We are most often formed and holding an image of ourselves, and yet in our depths and from within we can become subject to unknown elements and mysteries of our own and wider iterations of action and being. This is what an entire psycho-analytic assemblage is based on. While Deleuze and Guattari’s espousal of schizo-analysis – part of their own layered and unlayering extrapolation of being in terms of the geologic, the anthropoligic and ultimately in the name of an outside – as a procedure for re-ordering perception to arrive at lucidity (the latter concept and faculty explored to great effect in recent years in the work of Mark’s friend and collaborator Justin Barton).

*

Henri-Louis Bergson’s assertion that we routinely don’t understand the problems we face (seeing instead ‘bad composites’) gives us an off-ramp to a world of re-configured possibilities. The sense of unknown meanings and concurrences creeping through the bound walls of hard-fought, hard-built, spastically constricting reality momentarily prevail. Against the safety of everything switched off. We most often end up being a fraction of ourselves without knowing it and yet that otherness we routinely darken over into the unknown of the night remains, an insistence that we skim over like a low flying bat, splash our feet in occasionally, the unvoice we both revere and fear – that old unconscious voice of a different reality that cuts through to the core of things, and people – that thing remains.

It is this idea that we are simultaneously ourselves and things that are not ourselves, including the installations of childhood and the fabrics of the social-real, the blinded activity of concepts. And it is in this place of awareness that at some point – there are formations in abstraction that can occupy and inhere and find expression and perpetuation, that different spaces of perception become more populated by questions of what they are formed of and what they do, operatively speaking, affectively expressing.

The roaring of lions, the howling of wolves, the raging of the stormy sea, and the destructive sword, are portions of eternity too great for the eye of man.

William Blake; The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

The above quote, things Blake calls ‘too great’ for the eye of man and yet one suspects in some sense, they were seen by Blake in relation as to their ‘portions of eternity‘. Blake thus affirms the necessity of both their extraneity and their accessibility.

* *

the cosmic storm (Verve / Blake)

Blake’s London serves as the lyrical inception for another significant track, History (above) from The Verve’s sonically turbulent breakthrough album A Northern Soul from 1995.

The Verve had existed as a kind of wild northern English band specialising in vast swirling guitar sound and tight rhythm section grooves. Earlier songs from them like Man Called Sun and Gravity Grave were meetings with sonic expressions tumultous and harmonious, driven wild guitar spaces and melodies that charged the psychedelic-cosmic, while lyrically resonating the sun, challenging the gravity-as-death of gravity. Almost archetypal in their formation, four Wigan lads who were school friends, describing first hearing Nick McCabe’s guitar playing in their school as being like ‘another world’. There was also the fact that frontman Richard Ashcroft maintained in early interviews that he could fly.

Along with the general fact that they were simply wilder in sonic and inspirational terms than most of their peers – these things made The Verve a real outlier in their earlier years around the turn of the 90’s, their trajectory inflected with a sense of the mystical. Ashcroft described their beginnings as being an adventure, while incidents on their ’94 US tour demonstrated a proclivity towards excess and emotional / mental extremes.

Producer John Leckie had worked with the band on those earlier recordings (Gravity Grave and Man Called Sun had both appeared on the Verve EP in 1992) as well as for their debut album 1993’s A Storm in Heaven. I recall reading an interview with him a few years later in which he mentioned some regret at feeling never able to capture in their recorded sound, the extreme sonic forces unleashed with their live playing.

From those early tracks, it is however evident that Leckie tries to create an overall sound space conducive to melding their recorded work in a way that exteriorises it as much as possible from the pre-fabricated expectation of how those instruments and musicians might normally be recorded. Man Called Sun’s wind chime delays for example – caught in a strange and distended feedback, a cosmic miasma for saluting a personalised celestial evocation of being.

It’s me throwing stones from the stars on your mixed up world…

The Verve (Richard Ashcroft), Star Sail

The cosmic was entwined through this early work, a starting point of extraordinary potency and not only at work in the sound, but in Ashcroft’s singing and lyricism. The first track of their debut album (Star Sail above) a poetic explicit as reaching for the energy of motion of the stars, combined with its opening vocal of greeting from Ashcroft (‘hello it’s me it’s me calling out I can see you’) it becomes the irradiated frequency of a kind of sound sorcery, sonic forces expressing the star-filled tumultous void, suffusing and yet also beyond. Journeys necessarily verging into the heart of abstraction, aflame on a star-bejewelled wing of sound.

So while early on they were very much of a ferocious ethereality in flight and exploration, so their lyrical attention and sonic output would turn more to the micro-politics of socially destitute urbanity. The first line of their next single This Is Music would be ‘I stand accused just like you, for being born without a silver spoon‘. It was here on the album that followed, that their junction with Blake’s London occurs.

*

In time for recording their second album the band recruited Owen Morris (who would later gain prominence as Oasis’ producer) whose own wildness became known as part of these recording sessions, while relying upon a more direct sonic approach to what would become the 1995 album A Northern Soul. An album that crystalised the trajectory in two ways, on the turn away from the cosmically inspired psychedelia of their early work, towards sonics of a more traditionally alternative rock. It is the last of their work also that demonstrated guitarist Nick McCabe in mode as a dominant sonic force to the songs. Ashcroft had acoustic songs in there, in a melding that worked – but that would slowly wean the band from the frontier of squalling sonic transcendence as an effective vector – towards Ashcroft’s songwriting.

While there was still room for epic tumult like Stormy Clouds (and Morris and the band do still extend the sonic range here with string chords and reverb) as well the titular track itself. A Northern Soul‘s ridiculously effulgent guitar refrain made from wah and delay a prelude to its’ squally climb of a chorus – imbued with that mysterious lyric ‘There’s something inside of me, I don’t think I’m coming down…’

Despite this, the album’s heart seemed to belong to the track History, the soaring string epic based on an Ashcroft acoustic number, arranged as a string backed opus but centred on Ashcroft’s songwriting, the direction of the band’s sonic was becoming defined.

*

Lyrically Ashcroft had the bleak thread of the human-planetary condition running through his work and yet it remains striking that he turns to Blake (and London) for the album’s core emotional moment, and while it is Blake’s cadence that Ashcroft retains beyond those first few influenced lines – the poem echoes throughout. Stories of recording the album at the time had the band making use of ecstasy and other substances for entire sessions and even referenced producer Morris smashing the control room window in the studio with a chair when they’d recorded the track History. And somehow that intensity of emotion of feeling is there in the track, can be traced and lived again. Like Sparklehorse’s more direct telling, it becomes another embodiment of the same expression that Blake reached into, the living circumstance of human power structures, amid the wider cosmic context of seeing and perceiving that circumstance for what it is; a denuded, reduced, truncated and cognitively enslaved systematicity of power.

*

As some of the nature of our conceptual/cognitive predicaments resided with me while writing this piece, it became necessary to remind myself that there is another side to something like ‘Eternity is in love with the productions of time‘. That sense that in there being something ultimately beyond us, but in receipt/engagement in some way of our productions, that in the malleability of life’s hard definitions, arise that prospect of coming closer to the intensities that prevail in widening our apertures of awareness, in populating the dead-spaces of our perception. The real and material silence that opens the door to what is outside us, in both the operatively predatorial and the intensificatory.

***

One reply on “‘Eternity is in love…’ (Blake, Sparklehorse, The Verve)”

[…] wrote more about that here, while I am also reminded in general of this song, about Mark Fisher’s key assertion in […]

LikeLike